Methodology

Kia ora, first and foremost, I would like to acknowledge Janis Freegard for her work documenting the demographics of what’s published in Aotearoa. This work is directly inspired by her previous breakdowns, which can be found on her blog, and uses similar methods to compile its information.

Like Janis, I used a compilation of titles from the ‘Aotearoa New Zealand’ article of Literature, Critique and Empire Today (previously known as Journal of Commonwealth Literature). This article can be accessed for a fee from Sage Journals. I’m almost certain that this article doesn’t capture all the books published by all the publishers in the year, but it’s likely the most official source for NZ publishing.

The data I have compiled is on ‘poetry’, ‘adult fiction’, and ‘letters, auto/biographies and non-fiction’. I have chosen to omit anthologies, which are listed differently in the article, due to the nature of multiple editors and multiple contributors skewing the data.

Again, like Janis, to identify the gender and ethnic backgrounds of the authors, I search for information on the author if I don’t already know the information explicitly.

If there is consistent use of specific pronouns, I have assigned the gender associated with those pronouns. For authors using non-gendered pronouns, I have assigned them as ‘gender diverse’. As someone who has edited over 200 queer writers through my work on bad apple, I feel relatively confident I know which authors in 2023 identify as not cisgender. I also feel confident that there are trans men or trans women authors included in the 2023 statistics I’m sharing.

If there is no iwi identification or statement of other ethnic background, I have assumed the author is Pākehā. Authors who have a mixed ethnic background, Pākehā + Māori, for example, have only been counted in the Māori category. If an author has noted a mixed ethnic background (beyond Pākehā + xxx), they have been counted once in each category. I understand this may be contentious, but I think it gives the most accurate representation of which minority ethnic groups are represented.

As stated above, the data below is compiled using the 2024 issue of Literature, Critique and Empire Today. Specifically, the ‘Aotearoa New Zealand’ article for books published in 2023. The publishers who are present in this article and represented in the data are as listed:

5ever Books, Allen & Unwin, Anahera Press, Auckland University Press, Avon, Bateman Books, Bloomsbury, Bridget Williams Books, Cold Hub Press, The Cuba Press, Dead Bird Books, Flying Island Books, Giramondo, Gollancz, Greywacke Press, Hachette, Harper Collins, Harper Voyager, Hodderscape, Huia Publishing, Kowhai Press, Lasavia Publishing, Lawrence & Gibson, Little Brown Book Group, Macmillan, Matheson Bay Press, Moa Press, Massey University Press, Orbit, Orenda, Otage University Press, Penguin Random House, Piathus, Quentin Wilson Publishing, Scribner, Shadow Press, Simon & Schuster, Squabbling Sparrows Press, Steele Roberts Aotearoa, Sudden Valley Press, Tender Press, Text Publishing, Te Herenga Waka University Press, Titus Books, Ultimo Press, Upstart Press, YBK.

There are some books I knew were published in 2023 that were not included in the Literature, Critique and Empire Today article. The publishers not present in the article but represented in the data are:

Saufo`i Press

I may still be missing further publishers. Please contact me if you find something missing, and I can update the data.

Understanding the data

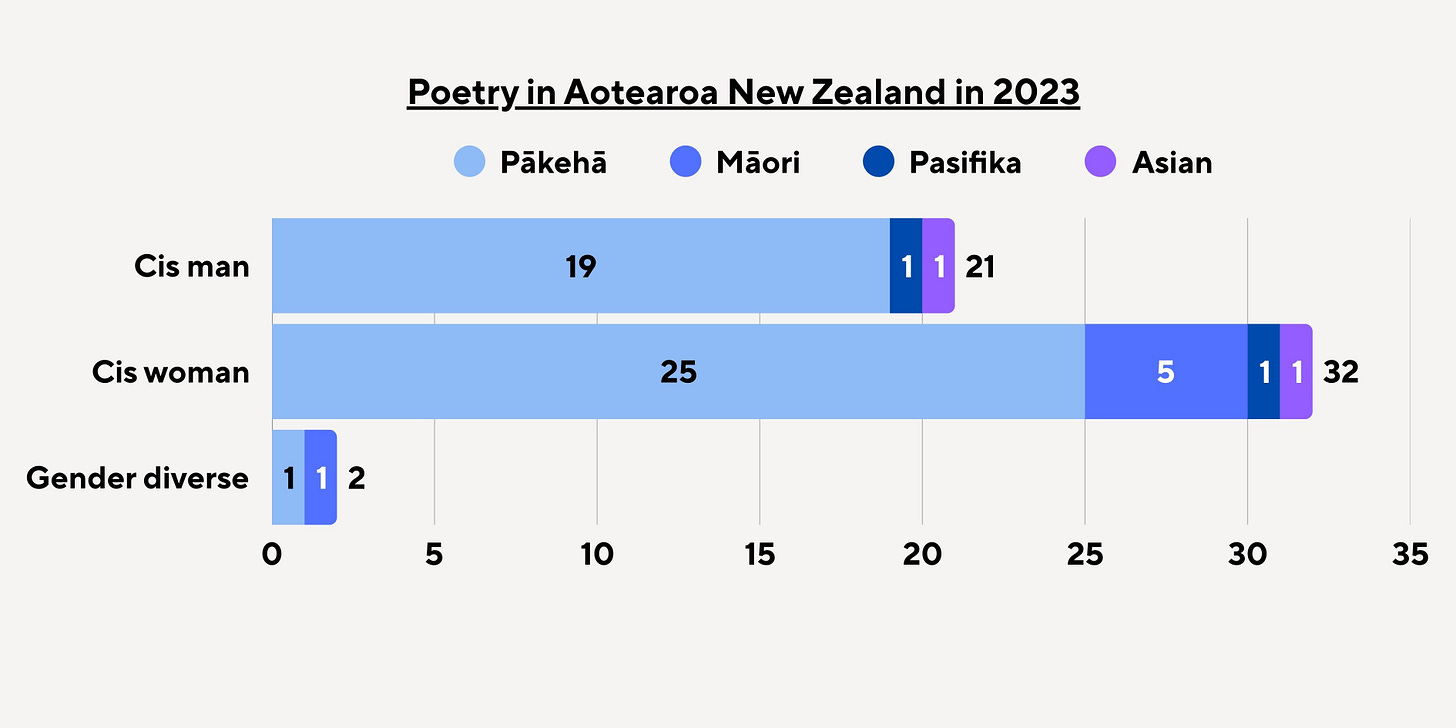

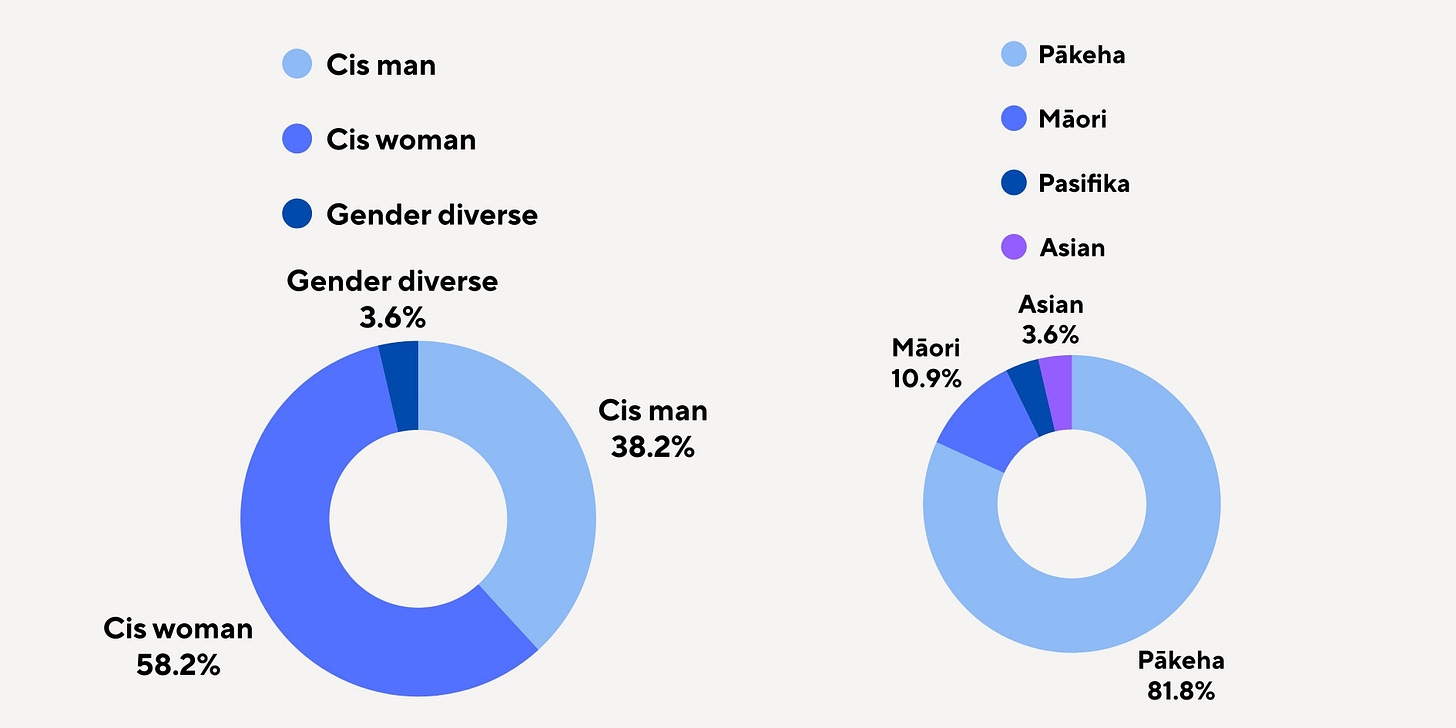

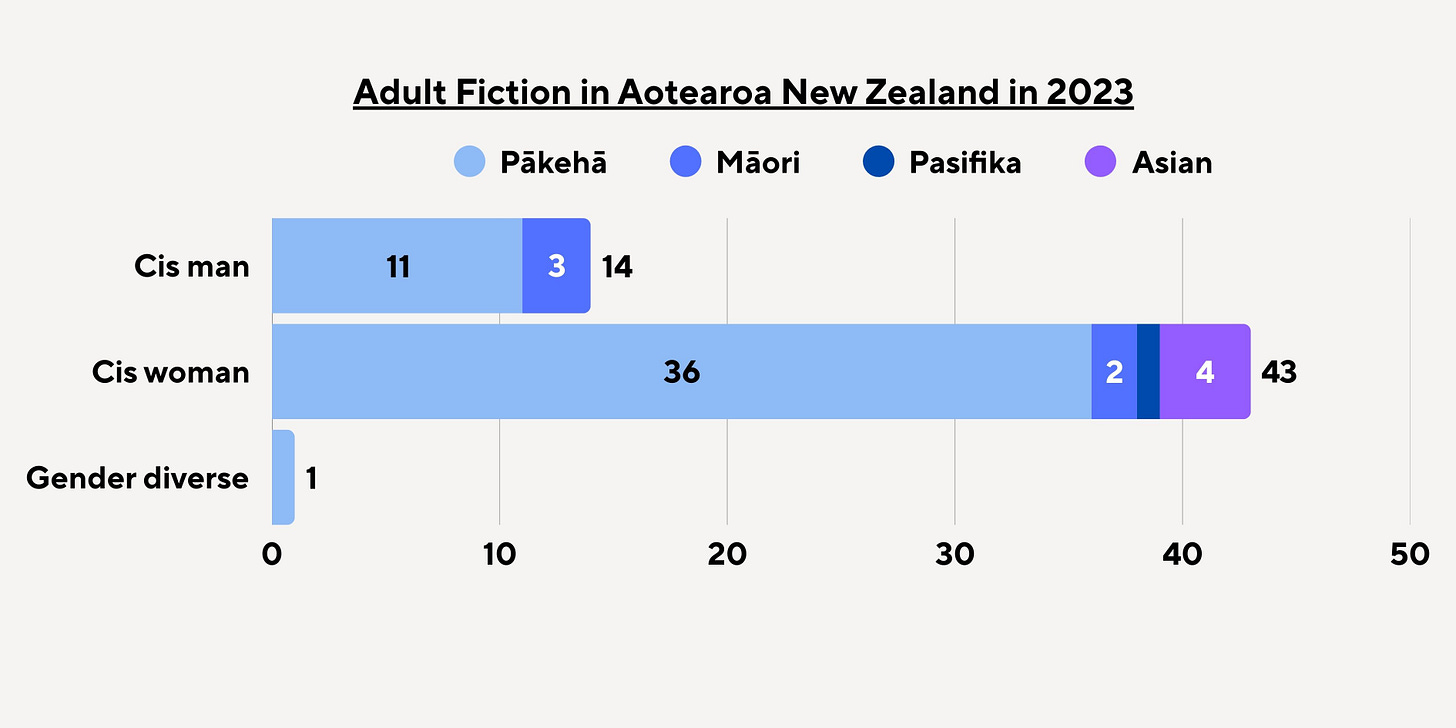

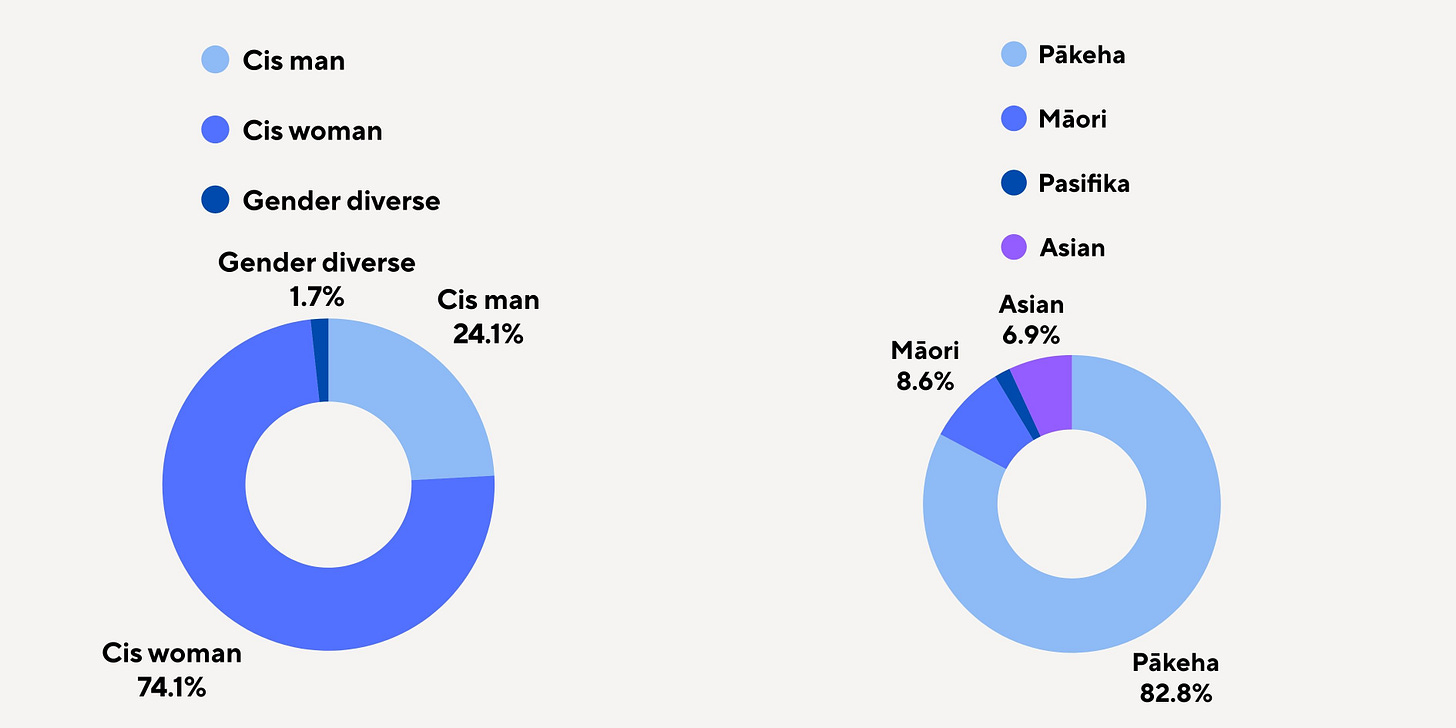

Hopefully, I have used clear graphs that illustrate the compiled data. Each category of writing is accompanied by a stacked row graph displaying the number of authors by gender and ethnicity, and two doughnut graphs with percentage breakdowns of gender and ethnicity in relation to the total number of authors.

Please leave a comment or contact me if something needs clarification.

Poetry

56 Titles by 56 Authors

Adult Fiction

59 Titles by 57 Authors

Letters, Auto/Biographies and Non-Fiction

15 Titles by 15 Authors

Conclusions

My goal is for this data to sit in context with the whakapapa of research done by Janis Freegard. Generally, I would say that fewer titles are being published across each category. Cis woman writers seem to hold the largest portions of poetry and fiction, but lag behind in the ‘non-fiction’. I think we may potentially find more cis women in illustrated non-fiction, which is not collected here. Ethnicity spread hasn’t really changed much since Janis’s 2019 or 2021 data—Pākehā are still published at significantly higher levels (around 80%) across all writing forms. Māori authors seem to be represented at a consistent level compared to Janis’s 2021 data. Due to Pasifika and Asian authors being published at such small rates, a single author can skew the data year on year.

Looking at the 2023 Census data, we can see that by proportion of the population, Pākehā (67.8% of pop.) are generally overrepresented in publishing compared to Māori (17.8% of pop.), Asian (17.3% of pop.), Pasfika (8.9% of pop) and Middle Eastern, Latin American and African (1.9% of pop).

Ultimately, I want this data to be utilised as a way to publish more books by minority groups. It shows that gender diverse, trans, Māori, Pasifika, Asian and MELAA authors are significantly underrepresented in publishing. If you’re a publisher or are interested in publishing, please consider this data when thinking about what books you want to put out into the world.

Thank you for taking the time to read through all my long-winded explanations for how I collected this data, why and what it shows us! My goal is to help address these gaps and imbalances in our publishing industry, and I’m always interested in supporting others willing to do the same! Please reach out if you want to discuss anything I’ve shared in this post or if you’d like advice on how to start publishing yourself!

Mauri ora,

Damien